Earlier this month, an airy new Jewel-Osco at 61st Street and Cottage Grove Avenue in Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood was bustling with shoppers and employees.

“This is nice and convenient, and there hasn’t been a grocery store around here,” said Sharon McGee, who stopped by the store after work to pick up a few things before heading home to Dolton. “I’ll be back to pick up groceries and for work potlucks.”

A few aisles over as she filled her cart with groceries, Hyde Park resident Suzanne Ruch was excited she didn’t have to shop at several stores to buy all the items on her grocery list. “I’m very pleased with how large it is, how bright it is, how clean it is and the produce is great,” she said.

Community stakeholders hope the long-awaited $20 million, 48,000-square-foot Jewel, paid for in part with $11.5 million in city tax credits, signals a new day in economically depressed Woodlawn. Despite its location — just blocks away from flourishing Hyde Park — it has struggled to recover from years of disinvestment and population loss.

With plans to locate the Barack Obama Presidential Center on the edge of the community — a development that has been slowed, in part because of a lawsuit to move it out of nearby Jackson Park — there’s a general feeling that the community may be getting back on its feet.

But there are challenges.

This isn’t the first time that investors, nonprofits, community advocates and residents have poured their energy and their money into a neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side, only to see the the main attraction — such as a retailer — open with much fanfare, only to limp along or worse, leave.

The closing of Dominick’s grocery stores across the city five years ago left several areas on the South Side without easy access to healthy food, and those voids have been difficult to fill. Its vacant store in the South Shore community will be the last site to be filled, by a Shop and Save that just last month finalized plans to buy the site and open its store later this year.

The absence of that kind of anchor has made it more difficult to lure other commercial and residential development, according to nonprofit and community leaders.

Last year, Target shuttered two stores on the South Side, the 126,000-square-foot Chatham store that opened in 2002 and a 128,000-square-foot Morgan Park store that opened in 2008 — despite plans to open two North Side stores in Logan Square and Rogers Park by 2020. The company said it was a business decision, not based on neighborhood or geography.

Englewood, which hoped the Whole Foods that opened in 2016 would pave the way for more businesses in the neighborhood — including the 30-plus local vendors stocking their goods on the shelves — remains a work in progress, nonprofit leaders say.

What’s creating hope among stakeholders of a real revitalization in Woodlawn is the opening of Jewel-Osco, which has 300 full- and part-time employees, and comes at the same time as other commercial, residential and transportation investments in the community.

A few blocks south of Jewel, at 63rd and Cottage Grove Avenue, Woodlawn Station, a mixed-use commercial and residential building developed by national nonprofit Preservation of Affordable Housing, recently opened with the well-known 127-year-old Daley’s Restaurant as one of its anchor tenants.

On the southwest corner of that intersection, the Cook County Land Bank Authority has announced plans to demolish the vacant 94-year-old Washington Park National Bank and erect a structure that will house a co-working space, a YWCA-managed entrepreneurial center and retail and banking businesses

Leon Walker, founder and manager of DL3 Realty, which developed the Jewel-Osco and Englewood’s Whole Foods store, will lead the project. “I’m focusing on how the grocery store is not just a place to get your groceries,” he said. “It’s a business opportunity for local vendors and entrepreneurs.”

So far, the Jewel has stocked products from 40 local vendors on its shelves.

Walker said he has plans for other projects in the neighborhood as well, although he declined to elaborate.

Housing is on an upswing as rehabbed and newly constructed housing units run along Cottage Grove Avenue and nearby. As a result, home prices are rising.

The median sales prices of one- to four-unit properties in the neighborhood soared 185 percent from 2010 to 2018, according to data from The Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University. That compares with a 72 percent climb in the city as a whole during the same time period.

Last year, Preservation of Affordable Housing, which has been working in Woodlawn for a decade, rehabbing, building and managing about 600 rental units, opened Trianon Lofts, a mixed-use retail and residential development of 24 two-bedroom apartments at both affordable and market-rate prices.

In addition to rehabbing homes in the community, nonprofit Neighborhood Housing Services of Chicago has provided education and financing for homebuyers. “These real estate developments get investors to look at communities they haven’t looked at before,” said Kristin Faust, the organization’s president,

On the public transportation front, the Chicago Transit Authority has made improvements to the Green Line station at 63rd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, and more work is expected.

In the past decade there’s been $410 million spent redeveloping Woodlawn commercially and residentially, driven in part by a $30.5 million U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Choice Grant given to the city and POAH.

The nonprofit plans to buy additional property in Woodlawn this spring for more housing, said Bill Eager, a vice president.

“We’ve always thought Woodlawn was chock-full of potential,” he said. “Its proximity to the University of Chicago, the lake and transit make it ripe for new investment.”

One result of the increased investment: a decrease in crime. Crime has plummeted by 51 percent from 2008 to 2018, according to data from the city of Chicago. (The data excludes homicides, which aren’t available in the database.)

“I think these are real signs of good things to come in Woodlawn,” said Robert Tucker, chief operating officer of the Chicago Community Loan Fund, which has provided over two dozen loans to businesses and nonprofits totaling more than $15 million in Woodlawn in the past 15 years, and was involved in the Jewel development. “When you have that kind of investment with a grocery store, you’re seeing that the community is active and the private market validates that.”

But advocates acknowledge that while a portion of the community is blossoming, the arrival of a big chain like Jewel is no magic elixir to quickly fix years of disinvestment.

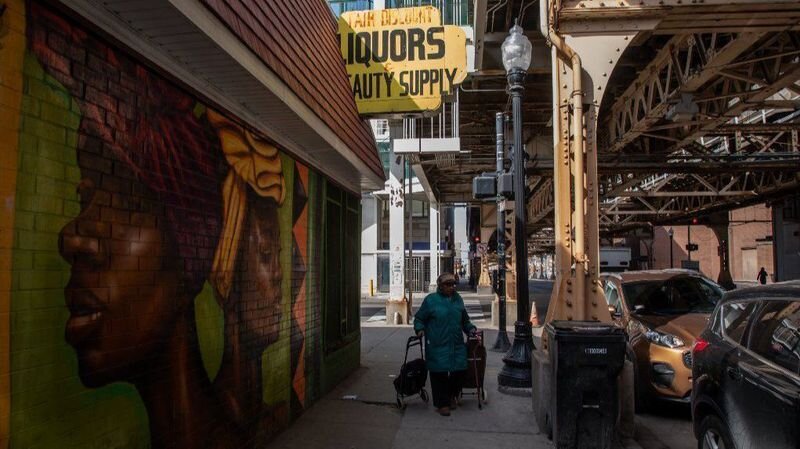

There are still shabby buildings and vacant lots, and the businesses are few and far between.

“One development can’t define a neighborhood’s revitalization,” said the Rev. Byron Brazier, a community leader who heads the Apostolic Church of God and 1Woodlawn, a community engagement and advocacy group. “We have come to understand that these developments are only stepping stones but how a community comprehensively addresses education, safety, and economic development will define its future.”

With the help of residents and other community stakeholders, 1Woodlawn developed a detailed strategic and economic development plan for the community by 2025. The goal is to transform Woodlawn into a business, residential and cultural destination without displacing current residents.

“A lot of us understand that a community that thrives has all those things together,” said Chicago Community Loan Fund’s Tucker. “You see developers and investors interested in the neighborhood, now people have to support them.”